As Boston’s Chinatown Changes, Asian Residents Face an Uncertain Future

- Cynthia Tu

- Dec 12, 2021

- 6 min read

By Cynthia Tu, Duncan Novak, and Anthony Labruto

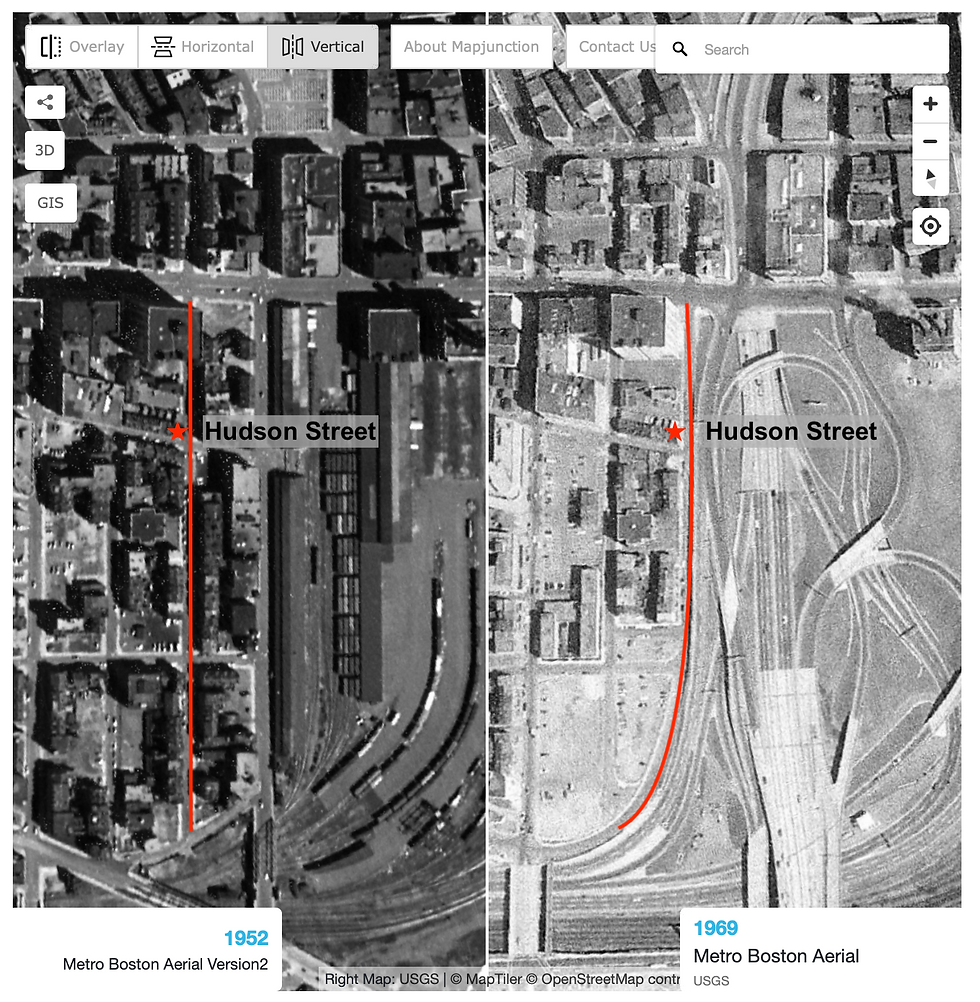

Born and raised in a row house on Chinatown's Hudson Street, Cynthia Yee calls her childhood in the 1950s "a paradise"— fathers all worked in the same restaurant, and mothers sewed together in the same factory. Yee and her friends shared bicycles and played rope on the street.

Yee’s carefree days in the thriving Hudson Street community quickly came to an abrupt end. In 1962, the Boston Redevelopment Authority’s construction of the Massachusetts Turnpike and I-93 highways displaced approximately 1200 residential units in the area. Yee’s Hudson family house was seized and demolished along with the entire east side of Hudson Street.

Yee’s family relocated to the outskirts of Chinatown, one block away from the adult entertainment district in downtown Boston. In her blog Hudson Street Chronicles, Yee documents the transition from the jolly Hudson Street to the clamorous red-light district, where prostitutes and police strolled around her house every night. “It was like going from heaven to hell,” she recalls.

Yee’s childhood story reflects the plight of the Chinatown community during Boston’s urban renewal project of the last century. After 60 years, the displacement crisis in Boston’s Chinatown has only become more devastating. With waves of gentrification crashing through the city and the nation in recent years, residents of this historical landmark for Chinese culture and history are still at risk of losing their homes.

The Disappearing Chinatown

For generations, Boston’s Chinatown served as a refuge for immigrants when they first landed in the United States. Since the 1870s, the Chinese community in Chinatown has grown slowly and steadily. Following the repeal of the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1943, the Chinese population further increased and diversified. The waves of Chinese immigrants built a tight-knit community to shelter its residents from anti-Asian sentiment. Boston’s Chinatown has been a safe haven for Chinese immigrants in Massachusetts, providing access to vital housing, multilingual social services, and entry into the American job markets.

Chinatown is now Boston’s most densely populated neighborhood, with an estimated 12,000 residents. Demographically, Chinatown is quickly becoming predominantly white. As the visualization shows, the White population is growing exponentially compared to a slowly stagnating Asian population over the past decades. Currently, Asian residents now make up less than half of the total population in Chinatown.

Meanwhile, Chinatown sees a huge racial disparity in household income distribution. According to StatisticalAtlas’ data on household income distribution by race in Chinatown, the majority of white households earned more than the Median Income of Massachusetts ($81,215), while 24% of Asian households fall under the poverty line.

With the shift in its population and demographic, Chinatown is undergoing change that endangers the lives and culture that the Asian communities had built over generations. By analyzing property data gathered by the City of Boston, it became clear that the housing crisis in Chinatown is further exacerbating as the area becomes more commercialized.

In 2020, Chinatown’s commercial buildings made up 30.48% of the total properties in the area, putting Chinatown the fourth most commercialized neighborhood in the city. In contrast, Chinatown ranked Boston’s second least residential neighborhood with only 5.54% share of residential property.

What comes with the commercialization of Chinatown is the rent surge. From 1990 to 2010, median rent paid by residents in Chinatown doubled from $1063 to $1960. The influx of real estate developers in the past years further worsened the housing crisis in Chinatown. Currently, the monthly rent for a two-bedroom apartment in Chinatown ranges from $2,500 to more than $6,000, according to zillow.com.

A survey done by MIT's Displacement Research and Action Network in 2019 revealed the staggering rent burden on Chinatown’s Asian residents. According to the survey, the average household surveyed earns an average of $26,280 per year, which is just above the federal poverty guideline for households of four people ($25,750). On average, each household spends an average of 48% of their income on rent. According to the MIT report carried out in Boston’s Chinatown, 24 out of 35 respondents reported that they were evicted due to rent burden, while four respondents reported being evicted due to conversion or ownership transfer.

The displacement issue faced by Asian residents in Chinatown reflects the plight of many tenants in Boston and nationwide. According to the Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University, more than 11 million households spend at least half of their incomes on housing.

In a recent study done by the Eviction Lab at Princeton University, researchers found that more than two million legal actions were filed in the country in 2016. According to data collected by the Eviction Lab Boston specifically had an eviction rate of 1.3%, which puts the city 178th on the eviction ranking out of more than 30,000 of large cities across America. This data means that 6.34 households were evicted every day while it does not count everything that has slipped through the courts or has failed to be accounted for by city data.

An Invisible Community in the Heart of Boston

Gentrification has inflicted destructiveness on the rich cultural aspects of a neighborhood like Chinatown. A survey done by the Chinese Perogressive Association revealed the importance of community, identity, and participation plays in the well-being of the neighborhood’s residents. 90% of the respondents reported that living in Chinatown keeps their connection close to the community.

The research also showed that redevelopment has disrupted the emotional state of the residents: 25 of 39 respondents replied that new developments in their area make them feel less secure in their neighborhood. It has become clear that the recent high-end housing developments in the neighborhood that are linked to increased costs of housing are not meant to benefit the Asian residents, but rather an incoming White population.

For the Chinese residents, Chinatown is their home where they feel an incredibly strong sense of belonging and community. It is where all of their friends and family live, where they shop for groceries, and where they want their kids to grow up. However, the commercialization and rising rent has pushed many out of their homes. What is concerning about this data is the well-being of the residents, as more are forced out of their homes due to higher costs of living and a growing commercial density. With the rapid commercialization in the area, the social spaces in the community are at stake.

In 2016, activists and Chinatown residents organized a protest after MassDOT’s intent to sell off Reggie Wong Memorial Park to real estate developers. However, the agenda of the protest was not to overturn MassDOT’s plan, but to appeal for developers to address air quality concerns in the replacement park which the developers were mandated to build. The park, located between the on- and off-ramps for the I-93 expressway, had continuously suffered from air pollution due to traffic brought by the highway.

These sacred community spaces, where children go out to play and elderly congregates, are being threatened by gentrification and development in the area. Many of the residents now feel insecure about living in Chinatown— the place where generations of Asian immigrants had called “home”.

What Does the Future Hold for Chinatown Residents?

In November, Michelle Wu made history as the first woman and Asian American to be elected mayor of Boston. With the recent election of Wu as mayor, many Chinatown residents feel a sense of optimism that they may finally have the representation they need.

Prior to Wu’s win, Wu released detailed plans for housing justice with actions to prioritize federal funds and reform zoning. Wu shared her vision to combat gentrification in Chinatown during a rally at the Chinatown gate: "It is urgent to ensure that we are stabilizing our families, and that’s why we need leadership at the local level apart from the government to do everything we can to keep families in their homes."

Although city officials had made promises to tackle gentrification, Cynthia Yee believes the word “gentrification” does not capture the essence of the housing crisis Chinatown has experienced for decades. From urban renewal projects to the influx of luxurious high-rises in the area, what continuously threatened the immigrant community in Chinatown is not solely class conflict, but racial injustice.

"It's really about who decides the use of the land and who decides they have a right to push other people out," Yee said. "Whether it's a highway or suburbanites wanting to live in the city, it's the same process of disempowering people of color."

For methodology and the data collection process, see here.

Download the parcel land use data used in our analysis here.

Comments